October 5, 2025

‘You can call me anything that you want but don’t ever call me a self made man’ is a quote from Arnold Schwarzenegger during a 2017 commencement speech at the University of Houston. It borrows from the popular idea that success is the culmination of hard work, sacrifice and dedication. While these variables are certainly essential skillsets, it reduces the ingredients until all that remains is an inedible stew that we call ‘grit’. The term was propelled to the mainstream by psychologist Angela Duckworth and it was shown to be a strong predictor of success. It refers to the amalgamation of passion and perseverance to achieve one's goals.

Once ‘grit’ permeated into the sporting sphere it became an essential trait for all athletes but it also normalized struggle and discomfort. While there is no argument that higher levels of grit will help athletes bounce back and persevere it can also teach athletes that because discomfort is necessary for growth, that it can also supersede their experiential thoughts and feelings. The term ‘pressure is a privilege’ is often used to normalize the pressure of performance and competition. It attempts to reframe competitive stress as a reward of sorts insinuating it would be unreasonable to complain about it. A better reframing would be to look at pressure as an opportunity to perform to the level that we can perform at. If we assume that grit is a trainable skill then the level of grit will change from athlete to athlete. With this in mind, each athlete will respond in different ways to the same stimuli and pressure exerted on them. One athlete's adaptive response to discomfort is a perfect environment for growth and positive self affirmation. Another athlete in a similar situation might respond with disillusionment and, over a prolonged period of time, eventual burnout.

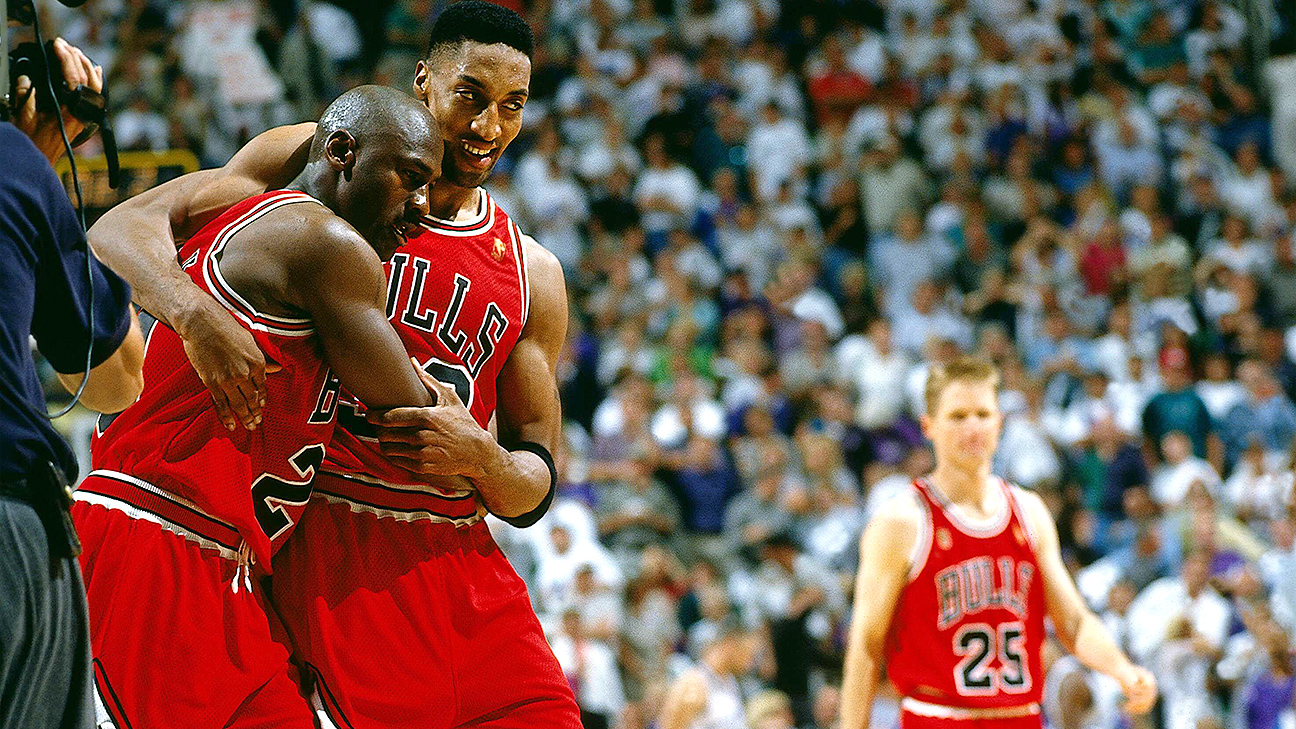

Coaches and recruiters want athletes to ‘be gritty’ and push through difficulties. They know that success and grit go hand in hand. This has lowered developmental age whereby these mental skills are not only being scouted but also being taught. It’s so very easy to compare two athletes and chalk the underperformance of one to them being missing something innate. At the highest level there is an understanding that there is a litany of gratitude to be bestowed once someone has accrued high achievements. Acceptance speeches echo thanks to parents, significant others, siblings and often the memory of them. Athletes wax lyrical about the support that they received from others and how it was instrumental for their success.

Developing athletes also require a support network to help mitigate the negative effects of having to perform in stressful environments. Athletes that have higher levels of social support tend to manage stress better and tend to have more positive psychological states. When athletes perceive social support, they also tend to feel more confident when pursuing longer term goals. These social support webs will include familial support (family), organisational support (brand or business), peer/team support (coaches/teammates) and professional support (sports psyc, physio). This mediation of basic psychological needs help support autonomy and perseverance. Additionally, this perceived social support has a positive correlation with grit both performatively in a sporting and academic context. From my experience, grit in sporting context is often labelled as being something that the athlete has to develop themselves but the athletes that often showcase grit are the ones that have consistent support systems in place. We should be advocating for and volunteering our support for athletes and emphasising that difficult times are not something we have to endure in private. The message we send during mental health awareness months should be echoed throughout the year. If you are an athlete, coach or professional and going through a hard time, reach out and talk to someone.

If you want to go fast then go alone. If you want to go far then go together.